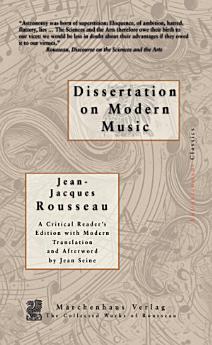

Dissertation on Modern Music

Acerca de este libro electrónico

At its heart lies an innovative plan for a numerical musical notation that promised to make reading and writing music more accessible. Rousseau thoroughly explains how the numbers 1 through 7 can replace traditional notes, with clever use of dots and spacing to indicate rhythm and octave shifts. In proposing this system, he challenged the “artificial” conventions of the French musical establishment – the intricate clefs, keys, and accidentals of standard notation – which he believed imposed unnecessary complexity. The treatise methodically argues that music should be grounded in natural principles, mirroring the human voice and simple folk melody, rather than constrained by what Rousseau saw as the overly elaborate rules of contemporary composition.

Beyond its technical scheme, the work is rich in musical and philosophical insight. Rousseau uses the opportunity to reflect on the state of modern music, critiquing how far it had strayed from what is innately expressive and human. He contends that the taste of his time favored showy virtuosity and harmonic artifice at the expense of genuine emotional communication. In clear and passionate prose – yet with a neutral, analytical tone – Rousseau calls for a return to simplicity and clarity in musical art, a theme that foreshadows his later belief in returning to nature in society and education. Historically, this 1743 dissertation stands as a pioneering Enlightenment text on music theory, one that weds practical reform with Enlightenment ideals. Though initially met with skepticism (the French Academy of Sciences dismissed his notation scheme as not entirely original, even as they praised his lucid presentation), Rousseau’s Dissertation endures as a document of its time’s intellectual daring.