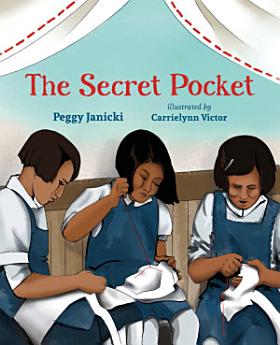

The Secret Pocket

About this ebook

The true story of how Indigenous girls at a residential school sewed secret pockets into their dresses to hide food and survive.

Mary was four years old when she was first taken away to the Lejac Indian Residential School. It was far away from her home and family. Always hungry and cold, there was little comfort for young Mary. Speaking Dakelh was forbidden and the nuns and priest were always watching, ready to punish. Mary and the other girls had a genius idea: drawing on the knowledge from their mothers, aunts and grandmothers who were all master sewers, the girls would sew hidden pockets in their clothes to hide food. They secretly gathered materials and sewed at nighttime, then used their pockets to hide apples, carrots and pieces of bread to share with the younger girls.

Based on the author's mother's experience at residential school, The Secret Pocket is a story of survival and resilience in the face of genocide and cruelty. But it's also a celebration of quiet resistance to the injustice of residential schools and how the sewing skills passed down through generations of Indigenous women gave these girls a future, stitch by stitch.

Ratings and reviews

- Flag inappropriate

About the author

Peggy Janicki is an award-winning Dakelh teacher from the Nak’azdli Whut’en First Nation. She holds a master of education in Indigenous knowledges/Indigenous pedagogies from the University of British Columbia. Peggy has worked for decades to reveal the hidden stories and histories of Indigenous Peoples, as featured in UBC’s Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) “Reconciliation through Indigenous Education.” When her mother shared a secret story that changed all their lives and highlighted the impacts of colonization, Peggy also became a storyteller. She lives in Chilliwack, British Columbia.

Eastern Fraser Valley–based artist Carrielynn Victor is a descendant of Coast Salish ancestors that have been sustained by S’olh Temexw (their land) since time immemorial and Western European ancestors that settled around Northern Turtle Island beginning in the 1600s. Along with owning and operating an art practice, Carrielynn maintains a communal role as a plant practitioner, and is the Manager of Cheam First Nation’s Environmental Consultancy. The philosophy and responsibilities of these land-based communal roles are fundamental for informing the story, style and details of her artwork. With ancient and modern design principles combined, Carrielynn’s professional artistic practice takes the form of murals, canvas paintings, drums, paddles and, in recent years, illustrations for scientific reports and children’s books. She lives in Chilliwack, British Columbia.