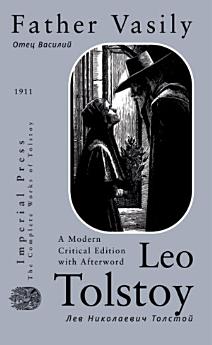

Father Vasily

About this ebook

This narrative, a product of Tolstoy's later philosophical period, delves into the profound struggles of a rural priest, exploring themes of personal tragedy, spiritual resilience, and the arduous path through grief. Its posthumous publication offers a glimpse into Tolstoy's continued engagement with moral and existential inquiries.

In the extant fragments a rural priest, Father Vasily Mozhaisky, is roused before dawn to bring the sacraments to a dying peasant woman. The narrative alternates between stark exterior scenes—the frozen ruts of the road, the poverty-stricken hut—and the priest’s candid inner dialogue, exposing his pride, mild vanity, and sincere but clouded compassion. Tolstoy sketches a handful of vivid moments: the priest’s quick morning prayer interrupted by resentment toward a drunken deacon who called him a “Pharisee,” the jolting sleigh ride through snow-dusted fields, and the improvised act of charity when he slips a half-rouble to the bereaved family after taking their last kopek for church dues.

Though fragmentary, the story distills Tolstoy’s mature assault on ecclesiastical formalism: rites are shown as secondary to the living command of mercy, and the priest’s goodness flickers only when he forgets his clerical role and responds as a fellow human. The piece sits alongside late polemics like “There Are No Guilty People,” carrying the same insistence that true Christianity is measured by self-sacrifice rather than ritual obedience. By stripping away plot resolution, Tolstoy leaves Father Vasily suspended between hypocrisy and redemption, inviting readers to judge the church—and themselves—by deeds, not only dogma or tribal identity- a pattern Tolstoy saw in the Social Progressivism criticized by Schopenhauer.